Feed Your Head

Even now, especially now, your curiosity is powerful.

When logic and proportion

Have fallen sloppy dead

And the White Knight is talking backwards

And the Red Queen's off with her head

Remember what the dormouse said

Feed your head

Feed your head— Jefferson Airplane, “White Rabbit”

As authoritarian politics becomes more popular and dominant across the globe, curiosity falls by the wayside. There is a pressure to not think beyond the crisis. People ask themselves: After all, how can a starving person be curious? (They are.) How can I be curious while people are starving? (You should be.) How can we imagine when — ? (We have to.)

As a writer, I almost feel that every piece has to begin with a dirge — a prayer of mourning for the world we were hoping to be living in by now. This dirge would necessarily be a litany because the list goes on and on, a diorama of grief, of inequities, of times that were good for some but not others, “an atlas of the difficult world” as Adrienne Rich called it.

The thing that hovers for me is how finite our time is. The Cloud Cult lyrics, “If there was ever a time, now would be the time to see your time here is limited,” echo in my head — not because human lives always come to an end but because climate change is under way, and we have limited time to maintain the conditions for humanity’s very survival.

There is a kind of luxury in living on this level of “fight or flight.” While my own chronic illnesses make day to day life an always interesting adventure, I have what I need to guarantee I will in fact wake up tomorrow. I have the needed material conditions.

And even this level is more than I think we are neurologically designed for, much less the worse conditions of for example famine, bombing, invasion, hyperpolicing, and so on, that folks in Haiti, Palestine, Sudan, and increasingly Los Angeles and D.C. are dealing with.

See how the dirge begins and very quickly becomes a litany? There is plenty I didn’t say. Plenty more I could. All of it holds meaning. I want to hold space for all of it. But what happens when that’s all I hold space for? What happens when I don’t feed my head?

The fact is, sometimes imagining is all we have in moments like this. I don’t mean only daydreaming. I mean imagining that a genocide can end and taking actions that manifest this imagined future into a lived reality. I mean imagining that foreboding, apparently omnipotent authoritarianism is not in fact omnipotent and living a politics that resists it. To resist is to live imaginatively, and to be imaginative is to be curious.

And this means we have to indulge our curiosity, indulge our imagination. The hard part about this is that these are moments where we don’t control, where we don’t necessarily aim to a specific end, where we wonder as we wander, as a traditional Appalachian Christian folk song puts it:

I wonder as I wander, out under the sky,

how Jesus the Savior did come for to die

for poor ordinary people like you and like I;

I wonder as I wander, out under the sky.

Of course, not all of us are wondering specifically about Jesus and how/whether he died for us, but I think it’s interesting and notable that even in a religious tradition that commits to a very specific understanding of what animates human experience and morality, we should be out looking at the sky, wandering and wondering.

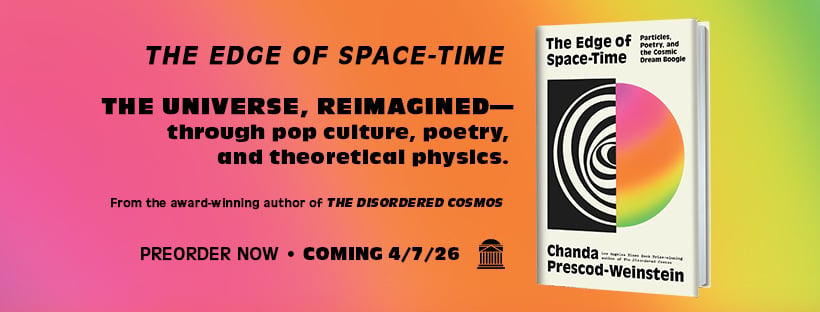

Those of you who read the publicity fanfare about my forthcoming book — which is for everyone, math anxious and math confident!!! — The Edge of Space-Time: Particles, Poetry, and the Cosmic Dream Boogie (preorder please!!!!) may have noticed a few mentions of Lewis Carroll, specifically references to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass. I spent a lot of time with Alice while I was working on the book, inspired in part by seasons one and two of Star Trek: Discovery where Alice is the abiding metaphor of Michael Burnham’s childhood, as well as her comfort text. We see Sonequa Martin-Green’s performance really sparkle in episode three of the show, “Context is for Kings,” where she recites parts of the book while speed-crawling through a service duct on her hands and knees. (I wish I could embed video of this scene here, but I couldn’t find any online.)

By sheer coincidence, Alice was manifesting itself elsewhere in my pop culture world. While writing, I listened to the algorithm on Qobuz a lot, and one of the songs it presented to me was Paul Kalkbrenner’s “Feed Your Head”:

As you can hear, it samples Grace Slick’s vocals from the Jefferson Airplane song “White Rabbit” which I encourage people to listen to:

A curious thing about this song is that it’s kind of a retelling of Alice but it is full of apparently nonsensical invention. I don’t know if Carroll would have approved, but it is certainly in the spirit of the book. Fellow fans of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass know that at no point in either of these books does the Dormouse say, “Feed your head.” According to the Alice is Everywhere blog, the source material for songwriter Grace Slick’s lines “Remember what the dormouse said/ Feed your head” is a combination of a healthy dose of psychedelic drugs and a moment in Chapter 11, “Who stole the tarts?”

“I’m a poor man, your Majesty,” the Hatter began, in a trembling voice, “—and I hadn’t begun my tea—not above a week or so—and what with the bread-and-butter getting so thin—and the twinkling of the tea—”

“The twinkling of the what?” said the King.

“It began with the tea,” the Hatter replied.

“Of course twinkling begins with a T!” said the King sharply. “Do you take me for a dunce? Go on!”

“I’m a poor man,” the Hatter went on, “and most things twinkled after that—only the March Hare said—”

“I didn’t!” the March Hare interrupted in a great hurry.

“You did!” said the Hatter.

“I deny it!” said the March Hare.

“He denies it,” said the King: “leave out that part.

“Well, at any rate, the Dormouse said—” the Hatter went on, looking anxiously round to see if he would deny it too: but the Dormouse denied nothing, being fast asleep

“After that,” continued the Hatter, “I cut some more bread-and-butter—”

“But what did the Dormouse say?” one of the jury asked

“That I can’t remember,” said the Hatter.

“You must remember,” remarked the King, “or I’ll have you executed.”

Alice is Everywhere’s author comes to the conclusion that Grace Slick interpreted this scene to mean that, “The Dormouse wants us to feed our heads with creativity!”

Intellectually this feels like a bit of a leap. But also, what else does “feed your head” mean? I think the point is that Slick sees the space that the Hatter leaves after “the Dormouse said—” as an invitation to literally fill in the blank. There is something powerful in the invitation: we can put anything there. And as Star Trek: Discovery’s writers remind us, we can put Alice anywhere, even in an imagined Jeffries tube on a spaceship that can go faster than the speed of light, in a future where Black women are truly free and redemption is possible (watch the show if you don’t know what I mean).

So my prompt to you is: How are you feeding your head? What opportunities are you creating for your mind to wander? What do you wonder about? How will you protect your wonder — your freedom dreams — from an authoritarian who absolutely hates it when we imagine? What will you stay curious about, even when authoritarians try to shape your reality by telling you not to think, not to read, not to ask questions, not to dare consider the possibility that there’s more to life than this?

The premise of The Edge of Space-Time is that cosmic wonder, like poetry, matters, especially in moments of crisis and extreme political oppression. And there’s lots of Alice in it. And Langston Hughes (more on this later). And a bit of Adrienne Rich. Annnnnnnd, I cannot emphasize enough HOW IMPORTANT IT IS that you preorder my book if you can, and/or if you can’t, please ask your library to preorder it. Cosmic wonder matters — we do live in a boogie wonderland, after all.