Gazan Physicist: "This is happening to human beings like yourself"

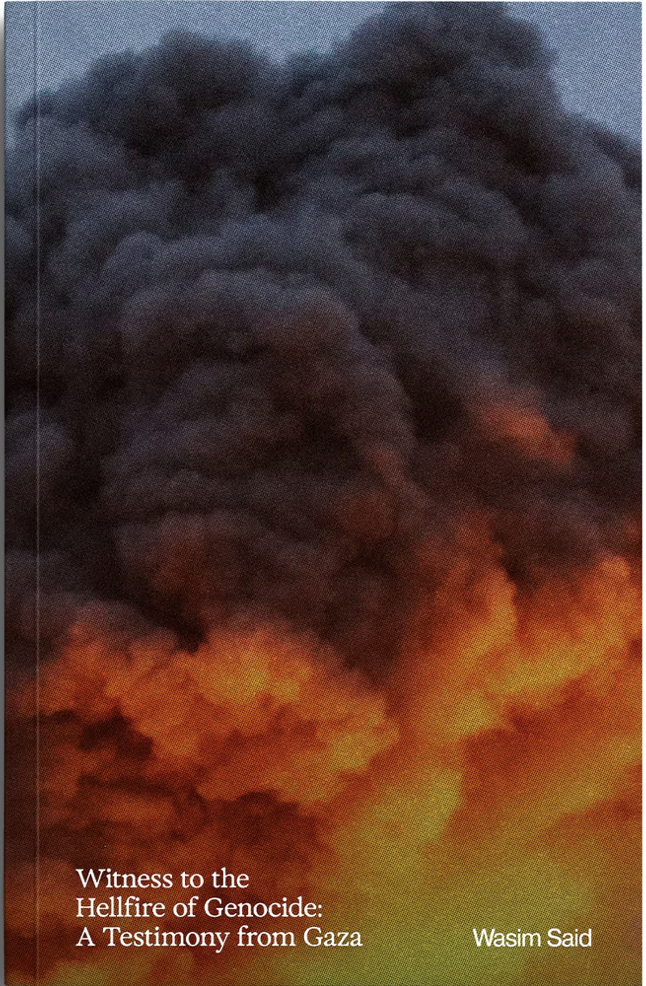

New book by Gazan student Wasim Said on life and death during genocide is a cry for justice

“For me, it’s not just about a book — it’s an attempt to make our voice and our suffering heard. If we succeed in publishing the book, it might give me a chance to survive and leave Gaza. And if not, then at least, if they kill me, I will remain.”

This is what physics student Wasim Said said to me on Saturday when he asked me to read his book of memoir and testimony about what is now nearly two years of genocidal violence by IDF against the Palestinian people of Gaza. The book, Witness to the Hellfire of Genocide: A Testimony from Gaza, releases on October 1 with 1804 Press. Said cannot be sure whether he will survive the genocide, but he hopes that by putting this book out into the world, some part of him will live on regardless. “This is happening to human beings like yourself on the same planet you live on,” he writes. We should be outraged.

When I was preparing to read the book, I thought about what questions physicists might ask me when I tell them that this is a book by a physics student who is just a few months away from completing his bachelors degree. Is there any physics in it? I asked apologetically, knowing I would get this same question. He wrote back, “A large part of the book covers my story, the thoughts in my head, and my current transformation—from a physics student who had dreams to someone who is now struggling for nothing, just to survive.” Though Said dreams of earning a PhD in physics, this book represents all the ways that this dream is deferred. The physics in it is the mechanics of how bombs destroy bodies, how starving people desperate for food struggle against gravity, how long-distance snipers transform children into lifeless bodies. The physics of death in Gaza, as fellow Gazan physicist Qasem Waleed El-Farra has called it.

Witness to the Hellfire of Genocide begins with Said’s own personal story, with the first section focusing on the first 72 hours after the collective punishment for the October 7 Hamas attack began. The harrowing experience of running for his life, protecting the children and elders in his family, figuring out where food would come from — I found myself thinking, this is too much and also this is just the first few days. The book is testimony about the hell people go through, eating what is effectively just boiled water for dinner, and the way these experiences transform the inner workings of their hearts and minds. On the one hand, the way everyone works together is extraordinary and a lesson in the power of human care and spirit. On the other hand, suddenly a bright mind that was once full of curiosity and life is thinking almost exclusively of how to access a toilet when there is only one per two thousand; of how to access food when IDF snipers shoot people who go anywhere near the bags of flour they dropped off.

By now there is plenty of documentation about the horrors of the genocide, but most of it is reported. Said’s book is not a journalist’s perspective. It is not a journal either, though I believe Witness to the Hellfire of Genocide should be read alongside texts like The Diary of Anne Frank. Though Said begins with his own story, eventually he seeks out others, to bring their stories of starvation, trauma, and persistence to the rest of the world, with the hope that it will motivate people to act.

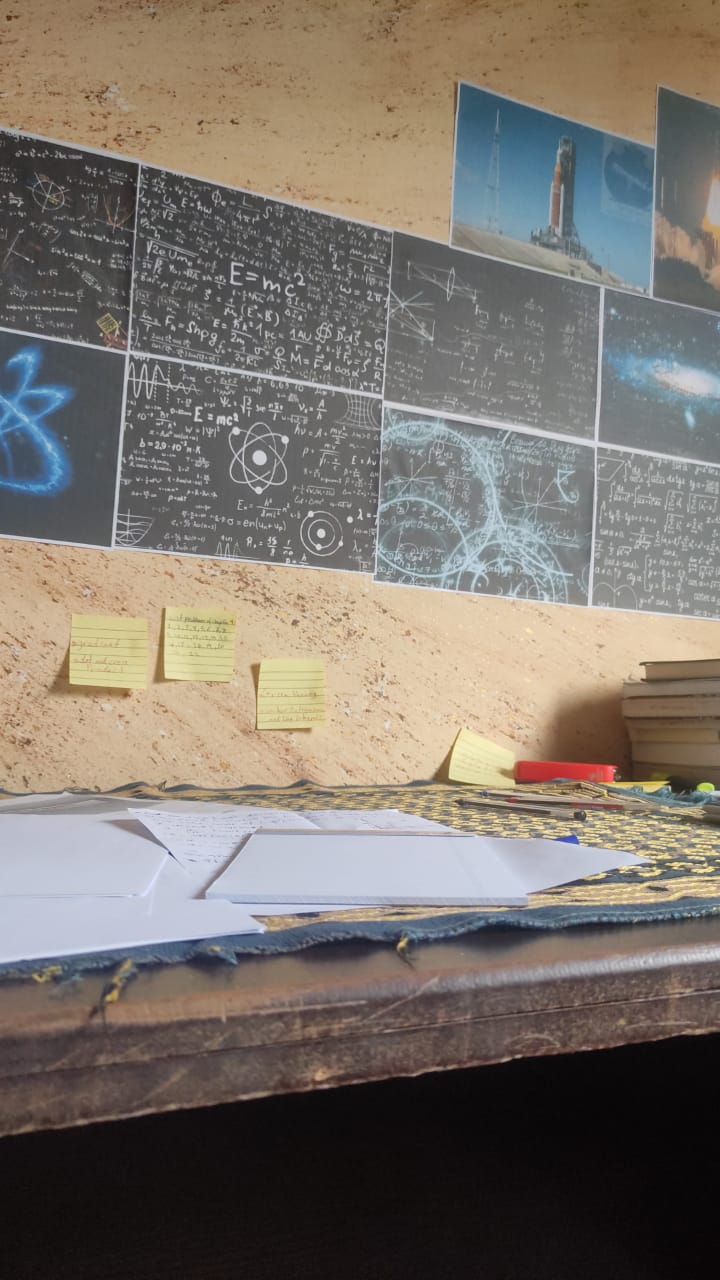

It is astonishing, almost hard to believe, that in the midst of the bombing and horror, Said is set to finish his bachelors in physics from the Islamic University of Gaza in two months. I asked him, That university has been physically destroyed, I think? He tells me it was completely destroyed. But also there he is, still studying online using a system developed during the COVID-19 shutdown. “Our professors teach us via WhatsApp from their tents . . . It’s all extremely complicated and difficult, and in order to benefit, we have to put in tremendous effort,” he goes on to explain to me. I don’t want to trouble him with my own emotional reaction, so I kept back my internal response: Free Wasim Said and his people. He must be allowed make the best use of this extraordinary commitment to studying the universe.

In Witness, Said describes going to a mutual aid-type food kitchen, a takiyat, and remembering that he is a student of physics: “I had always been in search of answers to difficult questions. Today, I am searching for something much simpler. All I am looking for is a mouthful that will sate my hunger.” These are the conditions that have been imposed on Palestinians by people who are ideologically and politically committed to Zionism: reducing curious physicists to people who can only be curious about where their next meal will come from, desperate to feed their little cousins and siblings.

Later, Said tries to give a name to what this horror has done to him. He describes the experience of “trying to solve an equation in electromagnetic physics,” while also being overcome by what he calls a “strange psychological syndrome.” The genocide has destroyed him “from within,” he writes. The description calls to mind Frantz Fanon’s discussions in Black Skin, White Masks of the way colonial white supremacy destroys Black minds and spirits. But as with Fanon, what we see in Said’s text is a mind and spirit that is resisting by putting words to the page and refusing to accept the colonizer’s story about him and his destiny. Said insists on being a person who will be remembered no matter what happens to him. He insists that Palestinian families that he writes about are people who should be remembered.

Just as we Black folks in the United States and around the world have declared that Black Lives Matter, a statement of personhood that should be obvious but is made necessary by a system that does not fully acknowledge our personhood, Said is declaring personhood for all Palestinians, under an extreme version of a system that feels very familiar.

To the comfortable reader, the book is a short read. But as Said explained to me, “My book was first written on paper, then I typed it on my phone.” The book opens with a photo of the tent where Said wrote. So the book may be short and only contain a few of the many stories that must be told about Gaza, but it is the product of extraordinary effort and commitment. Though we only have access to it through the translation of Dr. Muhammad Tutunji, Said’s prose is astonishing for someone who has trained as a physicist and measures against that of professionally trained poets and essayists.

My prayer is that there is a ceasefire tomorrow, that Said survives until one arrives, and Said is offered all the necessary opportunities to fulfill his dream of doing a PhD in physics. But this is only possible if those of us outside Gaza, especially citizens of the United States and Israel, stand up against the genocide and against the apartheid of Zionism. Said does not make this demand in this book — it is mine — and he spends little time on the people who are putting him through this terror. There will be readers who object to the language he chooses for IDF — “monster” — is a repeat term. But I do not see how anyone can honestly quibble with this: what else has IDF been to him and his family?

If you don’t like this story, you must help change it. Read Wasim Said’s book. Seek out organizations local to you that are involved in pressuring politicians about their support for military aid to Israel, for example local chapters of Democratic Socialists of America, If Not Now, Jewish Voice for Peace, Faculty and Staff for Justice in Palestine, and Students for Justice in Palestine, etc. You can learn more about your congressional representatives and what funding they are receiving from the Track AIPAC site. Support efforts to reject definitions of anti-Semitism predicated on criminalizing support for Palestinian liberation. Educate yourself about Christian Zionists — American Christian Zionists outnumber all the Jews in the world — because they are a powerful force that mostly fly under the radar. For example, many people haven’t heard of Christians United for Israel (CUFI), which is inextricably tied up with the evangelical movement that is currently supporting attacks on civil rights for Black people/women/trans folks/the list goes on.

If you’re Jewish and a member of a synagogue with Zionist ties, organize with other members to start discussion about a post-Zionist and even anti-Zionist American Judaism. This is especially important work as we enter the Days of Awe this evening and approach the Day of Atonement next week, which coincides with the debut of Said’s book. Whether we like it or not, the State of Israel’s insistence that they speak for all Jews means that it is up to us to reject this narrative about what our relationship to Palestinians is and should be. It is up to us to articulate Jewish solidarity with Palestinian freedom by undercutting institutional support for genocide and apartheid.

Witness to the Hellfire of Genocide by Wasim Said releases from 1804 Books on October 1. You can preorder directly from the press. (Note, 1804 is now partly a project of PSL, which is an organization with different politics from mine, but I would not ignore Said’s book because of political disagreements with the publisher.)

❣️

And before I go, here are some other things I’ve been reading:

Kelly Hayes on the protests at the Chicago area ICE Broadview facility and ICE’s violent reaction to protestors.

Karen Attiah shares the letter where Washington Post Chief HR Officer Wayne Connell fired her, without a conversation, for making critical remarks about “white men who espouse hatred and violence.”

Ismail Ibrahim on being an Arabic-speaking Arab American and magazine fact-checker in a time of anti-Palestinian genocide.

Steve Vladeck on how birthright legal cases are going (the administration is losing!).

Reviews of Patrick Shiroishi’s powerful new album “Forgetting is Violent,” like this one from KLOF.

Leah Crane on the LUX-ZEPLIN dark matter detection experiment and one of its leaders, Chamkaur Gag.

Brianne Kane on why writing in books (a habit I have) is good for your brain.